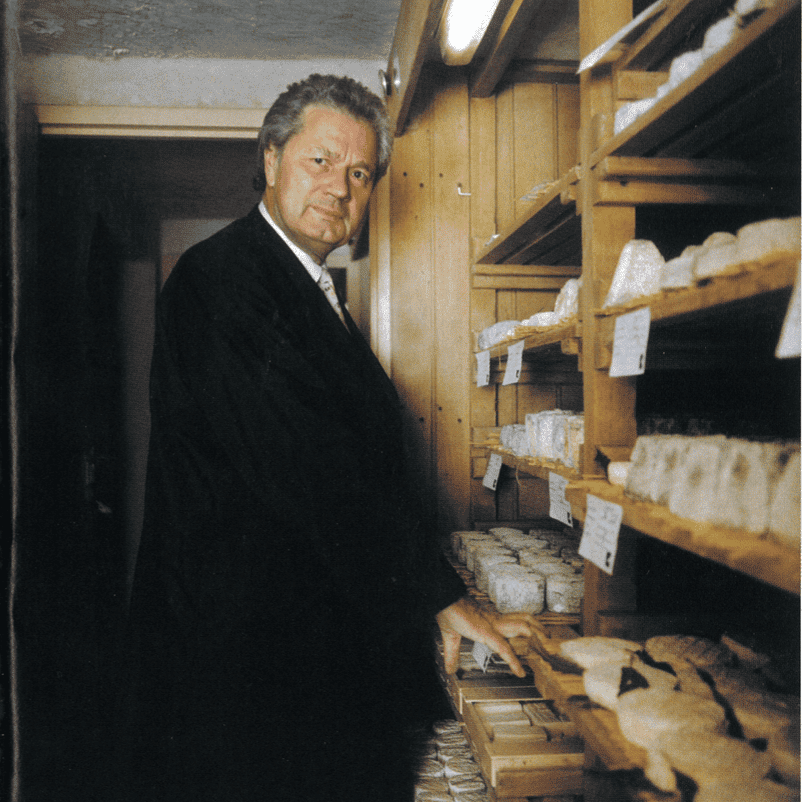

Philippe Olivier, the finest of affineurs

On his business card, Philippe Olivier describes himself as a "collector" and"expert consultant". An art dealer? He comes close. For him, cheeses are part of the national cultural heritage, to be kept alive and sometimes restored. Thirty years of keeping them alive, and sometimes restoring them. Thirty years of defending a masterpiece, in his eyes: local cheese made from raw milk.

In the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, Philippe Olivier is known as the Maroilles. In Boulogne-sur-Mer, this colossus' small boutique offers one of the finest selections of cheeses in France. Seventeen people look after the shop, which generates sales of 4 million euros, up 20% year-on-year.

France's best cheesemaker in 1996, president of the Syndicat national des crémiers, fromagers-affineurs de France, chevalier de l'ordre national du Mérite, lecturer all over France and as far afield as Tokyo and Dubai, the man is part of the northern elite that Nicolas Sarkozy invited to the Elysée Palace when he screened Bienvenue chez les Ch'tis.

And yet, there's no show-off, no chatter from the almost sixty-year-old businessman to whom everything has been a success. Philippe Olivier tells the story of a life devoted to unearthing the best cheeses in the countryside. The son and grandson of Normandy grocers who were already into Camembert, he could have been disgusted by it.When we were kids," he recalls, "we only went to the beach in the afternoon when we'd turned over the neufchâtels in the cellar, and of course we only ate the very strong, runny ones from the store...". But this"living, fragile, anything but canned" product appealed to him. He opened a store in Boulogne-sur-Mer in 1974, at a time when the development of supermarkets seemed to be dooming small-scale food retailing to a rapid demise.

Aiming for the top end of the market, not selling off the production of the large dairy industry, but offering artisanal cheeses, accessories and advice: the cheesemonger has a decade's head start in the boutique-concept. Boulonnais customers are quick to let him know. They come out railing,"It calls itself a cheese shop and doesn't even have Babybel!"

Extensive questioning

So, to prime the pump, the cheese maker reinvents marketing. At the city's most famous restaurant, he offers sumptuous cheese platters on condition that they are displayed at the restaurant entrance. Customers take the bait, increasing their consumption of wine, which does not leave the restaurateur unmoved. The tray can become a paying item, and competitors follow. Soon, luxury hotels all over the world were placing orders. Today, exports (to some fifteen countries) account for 60% of sales.

In France, he only has stores in Boulogne-sur-Mer and Lille, and supplies a handful of top Parisian chefs from the Nord region. That's all, "I know it's far-fetched from a business point of view, but I have very strong links with around fifteen cheese-making and refining colleagues all over France." Impossible to compete."When someone finds a good little pélardon somewhere, they call me..."

Philippe Olivier has no intention of buying from anywhere other than his favorite small-scale producers. A visit to his store quickly turns into a portrait gallery. Each cheese has its own family and its own story. Maroilles? "A friendship with the Gravet family. We developed an exceptional cheese, which is sold after a hundred days of maturing, when most are sold after a month. Soft! If you cut it in half, there's nothing chalky about it - it's all heart.

The producers who approach him undergo a thorough interrogation: breed of the animals that supply the milk ("a Camembert that tastes good is made with Normandy cows, not with milk pissers"), geographical area of production, size of the farm, milk storage conditions, method of production and maturing, quality of packaging...."The difference between a good enough cheese and an exceptional cheese is all in the details."

Driving all over France, taking part in small regional competitions to find the pearl, the cheese made according to the rules of the art, sometimes for domestic use only. And convincing producers to sell them. It's this meticulous and delicate work of "collecting" that Philippe Olivier loves. Above all, don't ask a small producer for 50 cheeses a week from the outset. "Otherwise, he'll say to himself that he'll have to invest, but that one day, this guy might let him down...". Visiting him five or six times. At first, standing in the courtyard in the rain, a quick hello because we were passing by. Then coffee around the farm table. One day, we have lunch. We talk about everything but cheese. The next time, we've sent flowers for the boy's communion, and we ask if everything went well. Trust is established.

Only then:"I'd love to sell cheese like yours, but you make so little...""For you, Philippe, I'd make a few." Don't order."You put a few aside for me, as you can" It's well paid, it's regular. Some time later, you dare to ask for more... these relationships forged, certain cheeses sometimes come back to life. Recipes emerge from the cupboard or from the memory of a mother-in-law ...

Philippe Olivier regularly rescues lost productions from oblivion.

Then comes the maturing process. Another subtle operation, another skill that the cheesemaker reveals to us.

"like the maître de chai for wine, it's a matter of taking time and care in the cellar to bring the cheese to an optimum for tasting." In his cellar, under the store, in semi-darkness, shelves on all sides. Depending on their position, the cheeses benefit from different temperatures and humidity. The floor is a mixture of earth and charcoal; the elm or beech on the shelves is cut as the moon rises; the cheese is turned, brushed or washed daily with champagne or burgundy marc, cider or craft beer, depending on its region of origin.

Philippe Olivier regularly rescues lost productions from oblivion

everything succeeded. Philippe Olivier tells the story of a life devoted to unearthing the best cheeses in the countryside. The son and grandson of Normandy grocers who were already into Camembert, he could have been disgusted by it. As a kid," he recalls, "we only went to the beach in the afternoon when we'd turned the wind over. Soon, luxury hotels all over the world were placing orders. Today, exports (to some fifteen countries) account for 60% of his sales.

In France, he only has stores in Boulogne-sur-Mer and Lille, and supplies a handful of top Parisian chefs from the very beginning.

Driving all over France, taking part in small regional competitions to find the pearl, the cheese made according to the rules of the art, sometimes for domestic use only. And convincing producers to sell them. It's this meticulous and delicate work of "collecting" that Philippe Olivier loves. Above all, don't ask a small producer for 50 cheeses a week from the outset. "Otherwise, he'll say to himself that he'll have to invest, but that one day, this guy might let him down...". Visiting him five or six times. At first, standing in the courtyard in the rain, a quick hello because we were passing by. Then coffee around the farm table. One day, we have lunch. We talk about everything but cheese. The next time, we've sent flowers for the boy's communion, and we ask if everything went well. Trust is established.

Only then: "I'd love to sell cheese like yours, but you make so little..." "For you, Philippe, I'd make a few." Don't order. "You put a few aside for me, as you can" It's well paid, it's regular. Some time later, you dare to ask for more... these relationships forged, certain cheeses sometimes come back to life. Recipes emerge from the cupboard or from the memory of a mother-in-law ...

Philippe Olivier regularly rescues lost productions from oblivion.

Then comes the maturing process. Another subtle operation, another skill that the cheesemaker reveals to us.

"like the maître de chai for wine, it's a matter of taking time and care in the cellar to bring the cheese to an optimum for tasting." In his cellar, under the store, in semi-darkness, shelves on all sides. Depending on their position, the cheeses benefit from different temperatures and humidity. The floor is a mixture of earth and charcoal; the elm or beech on the shelves is cut as the moon rises; the cheese is turned, brushed or washed daily with champagne or burgundy marc, cider or craft beer, depending on its region of origin.

Back to local

"Cheese doesn't taste the same depending on what the animals eat or the weather, because the milk is different. A good cheesemaker smoothes out these irregularities.

He knows that if Brie is made on a rainy day, it will run. So it has to be placed high up near the ventilation system to dry. But if you make Brie on a dry day, you need to moisten it close to the ground. The Japanese, to whom the master refiner tries to teach the rudiments of the trade, are baffled. "They point out that I don't always say the same thing. So, for them, it's not serious!"

Recently, a number of major French cities have been calling the Syndicat des fromagers-affineurs. They want a real cheesemaker in the city center, and are ready to help him set up shop. In the specialized food sector, this is now the most promising niche, along with organic groceries. And the number of small cheese producers in Nord-Pas-de-Calais is growing again, observes the entrepreneur. "I sometimes seem to be talking about the past. But the future, in contrast to globalized food, lies in a return to the local." On one condition: that it's well done.

Directed by Le Monde

Discover another article